Since the beginning of music history, queer artists found spaces to express their identity among the different genres, leaving an imprint of themselves and everything they stand for in the most hidden parts of everyday music.

The following piece is in no way a wide-ranging description of all the contributions left by queer people in music since they’re so ingrained into its history that it would be near impossible to acknowledge everyone. It’s just a little taste, aiming to introduce us to a world that still remains mostly unknown, simmering under the surface, yet having contributed to the foundation of most of the music we love today.

Blues (1870s-1940s)

Rhythmic, rebellious, a scream of desperate melancholy: it’s here, in blues, that the earliest contributions by queer artists are recorded, a genre rooted in the American Deep South of the early 1870s, blossoming from the cultural traditions established by enslaved people of colour. Despite the consequences brought on by the American Civil War (1861-1865) and, more specifically, by the ratification of the 13th Amendment that – in theory – abolished slavery in the United States in 1865, in fact, the emotional toll experienced by Black Americans with slavery and the enduring socioeconomic oppression that persisted long after, inspired some of the most famous themes of early blues.

It’s popular knowledge that blues is inherently linked to Black people and therefore to the Black Experience, but it’s a less-known fact that it was also fertile ground for queer artists to subtly express their identities, especially women. Some of the household names, that emerged in early 20th century America, are Bessie Smith (with Empress of the Blues), Lucille Bogan (with B.D. Woman’s Blues), and of course, Ma Rainey (with Prove It On Me Blues), recently brought to popular attention by the movie starring Viola Davis and the late Chadwick Boseman. These artists rely on explicit references to their queer identities in their music, but they aren’t the only disruptors of the genre: other singers like Sister Rosetta Tharpe or Sippie Wallace challenged the traditional ideas of femininity by way of dressing and acting.

Blues eventually evolved, and throughout the prospering 1900s jazz communities, provided fertile spaces for more queer artists to thrive.

Disco, Electronic, House (1970s-today)

If “Queerness in Music” was an album, these genres would be its titular track.

Born in the second half of the 20th century, disco, house and electronic, saw the rise of LGBTQ+ contributions to music. The time of these genres’ rise gallops through the ‘70s and ‘80s, years constellated by the growing popularity of rock and pop music, and strongly supported by the “sexual revolution” of the ‘60s.

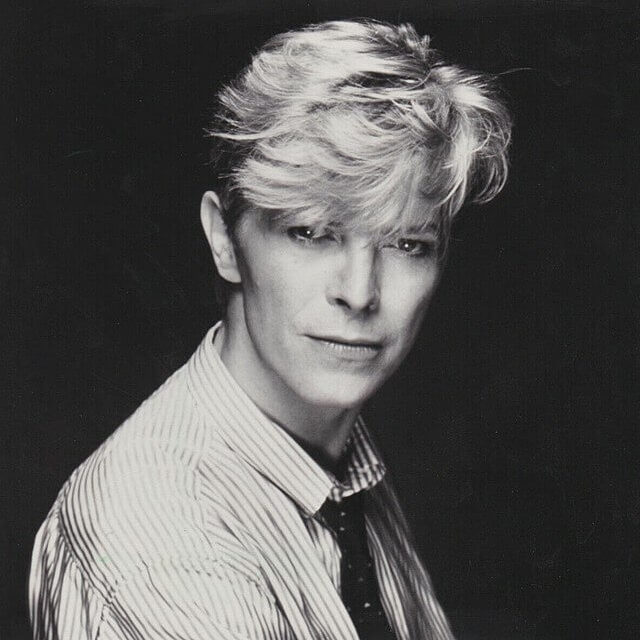

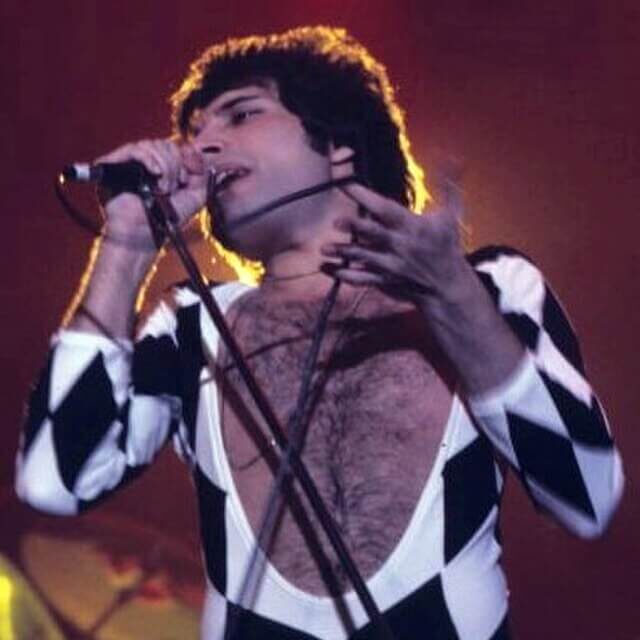

Sexual fluidity allowed performers like Grace Jones, David Bowie, Prince and Freddy Mercury to exist on that fine line of ambiguity that did not force them to define their identities but created a safe space around their music for the queer community to exist and thrive.

These big names of glam rock and pop are just the tip of the iceberg though, because larger, bolder communities existed in the submerged scene: disco culture, in fact, is directly associated with black and queer artists since its beginning. The so-called “ballrooms”, underground queer clubs springing up in big cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York saw the blossoming of “drag house culture”, a safe space for the LGBTQ+ Community to exist fiercely, to thrive harmlessly, to grieve collectively for the upcoming AIDS epidemic that would soon bring millions to their knees. “Drag house culture” is one of the most important movements for the Community, gatherings to the “balls” to party and dance on Saturday night, and providing safe houses through the week for thousands of teens kicked out by their families for being gay or trans, and otherwise forced to “turn tricks” and live dangerously on the streets. Disco was a way of life, and it’s also thanks to this Community that it turned into the soundtrack of the ‘80s, creating even more iconic trends, like the Vogue dance style.

Today this subculture has come above ground, growing in popularity and influence, inspiring big-name artists like Kesha, Drake and even Beyoncé (her latest album, REINASSANCE, beyond being highly danceable and house, features queer icons like Moi Renee, Big Freedia, Honey Dijon and Grace Jones).

It’s remarkable how pivotal and queer this genre was to the ‘80s, accompanying by hand the advancements in gay culture and LGBTQ+ identity.

Rock ‘n Roll (1950s-1970s)

Let’s take a step back to the ‘50s, for a second, let’s search for queerness where its role isn’t so apparent. Let’s take a broader look at Rock in its entirety, at its founders, the ones who have been cast aside, hidden in the shadows because of their identities.

A pillar of Rock, someone who was there since its origins, is Little Richard (born Richard Wayne Penniman), the pathbreaking piano-rocker whose songs still resonate in US diners and on school reunions’ dance floors. He made the combo “train drums” and “vigorous screams” timeless, inspiring and training legends like Rolling Stones, David Bowie, The Beatles, and James Brown.

The self-proclaimed Architect of Rock ‘n Roll, wasn’t your ordinary, run-of-the-mill, rocker: he wore eyeliner, acted out against his homophobic father, and described himself as gay at a time that wasn’t exactly welcoming. He spent his formative years around queer-like nightclubs, drag queens and icons like the already-mentioned gospel guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe. His non-conforming identity was the result of a pre-existing bubbling culture that was impatient to come to the surface, resulting in the acceptance of a feminized Black man by a white, racist, and homophobic audience, probably especially because he was perceived as less threatening than others. This doesn’t mean that Little Richard was immune to cultural appropriation, or even worse, obliteration. In a 1990 interview with Rolling Stones, he recognised his own struggles, tackling the controversial role of Elvis Presley in the history of Rock, especially the covers Presley made of originally black songs (one of those Tutti I Frutti, by Little Richard himself). Even if in the bio-drama movie Elvis (2022), Presley (played by Austin Butler) is shown as well-integrated with the black community and even as being friends with Little Richard, in the aforementioned interview, the Architect confesses: “I think that if Elvis had been black, he wouldn’t have been as big as he was”.

Little Richard struggled at length with his queerness, intended as being present in a form that differs from what is required and expected, and not simply as identifying as gay. At various times in his life, he renounced his past work and character because of his alignment with conservative Christianity. Nevertheless, his example liberated artists like Mick Jagger, Miley Cyrus and Lil Nas X to seduce and scandalize on stage all in one set, and his contribution as the queer founder of Rock ‘n Roll remains in the History books.

Punk (1970s-1990s)

The second half of the 20th century saw the rise of punk music, a genre wholly built around the concept of questioning and rejecting social norms. This exact definition is the reason why queer people clustered to punk since it provided the freedom to express and explore their identities in the predominantly white and male-dominated scene. Sexism and a lack of intersectionality within the group were of course still present and redundant, typical of the times, but punk has undoubtedly had an affinity with sexual outsiders since its beginning. The most redundantly iconic faces of punk, in fact, are over-the-top outsiders: from the Sex Pistols wrapped in bondage to the immense Vivienne Westwood (who gave punk its leather-wrapped, spikes-filled look) and her boutique SEX at 430 King’s Road, London. The same street, by the way, where only a decade prior, fashion designer Mary Quant launched the miniskirt.

Even the name, “punk”, has queer origins: in Shakespeare’s English it referred to a female prostitute, and later on, to young fellows selling sex to older gentlemen. In general, a “punk”, is a person aiming to do something socially aberrant or disgraceful.

Punk is and always has been all about anarchy, anti-sociality, reclaiming freedom, and noise, so much noise it deafens the boring, norm-abiding bigots. Punk is pioneering, ironic, political, angry and apathetic. Still, everlasting in its questioning prowess.

An example of this chameleonic skill? Jayne County (frontwoman of Queen Elizabeth and Wayne County & the Electric Chairs), broke the punk scene as the first openly out trans woman in rock in 1979, after spending her twenties thriving in the Atlanta drag scene and landing in the bohemia of late ‘60s New York, where she participated in the Stonewall Riots (June 28 – July 3, 1969).

The ‘90s were the decade of Riot Grrrl, a subcultural movement that combines feminism, punk music and politics, aiming to normalize female anger and celebrate women’s sexuality. Thanks to this movement, which turned out to be one of the most influential feminist movements of all time, slowly but surely, songs by queercore bands like Team Dresch reclaimed queer language in a scream of rebellion, and “Rebel Girl” by Bikini Kill echoed throughout 1992 with conceited lyrics sung by everyone: “in her kiss, I taste the revolution”.

But this primarily white movement wasn’t the only one to rise in the late ‘90s: the feminist mother of Afropunk, Sista Grrrl Riots, provided a safe space for Black, Brown and BIPOC women to revolutionize music with their own truths and experiences, with founders Tamar-kali Brown, Maya Glick, Simi Stone, and Honeychild Coleman emulating the Charlie’s Angels on their flyers, exposing and contesting the exclusive “whiteness” of Riot Grrrl.

It’s within those two movements that “zines” were born: homemade publications of art, opinions, and writing, shared hand by hand throughout the cities. Quick-moving and rebellious, zines acted as a secret gateway for women to share and discuss safely among themselves controversial, political and taboo issues like eating disorders, rape, and domestic abuse. Pushed to popularity by the efforts of people of colour and those in the LGBTQ+ Community, tackling large-scale personal and political matters in small circulations, zines soon turned into a celebration of independently published and underground magazines, fundamental to the development of free speech. Today, they survived the digitalisation of the 21st century, turning into webzines. The nomenclature and its evolution are only of partial importance though; it’s their objective that remains, we still use zines as the same outlet: a form of freedom embedded in words of knowledge and mutual exchange.

Photo by Raph_PH on Flickr

Indie Rock (1970s-today)

Noncommittal, ambiguous, absurd, out-and-proud, refusing to represent itself under conforming terminology: that’s indie today. Or at least what is perceived as such by the masses, according to convenience. In the ‘70s, when it first emerged, indie rock was much more conservative. Mainly because it moved by inertia and awkwardness through an audience of white, hetero men, forced into hiding by a weird kind of shame. This exact growth in itself is a little like queerness: being compulsorily pushed into little boxes and a silent-like existence in the origins, to then be famous, seemingly accepted, yet mercified.

Unlike dance, which grew in popularity in the hearts of the big cities, indie rock stayed hidden away in the monotonous and safe suburbs. The band B-52’s, for example, carried with them under the surface a kind of queerness that was accepted because not explicated. In the ‘80s the intention was still to shock the “All-American Man” tendencies that prevailed, and B-52’s tried to do so with drag-inspired mockery. The B-52’s also played a pivotal role in the activism aimed to acknowledge and shine a light on the horrors of the AIDS epidemic; maybe because Cindy Wilson was the only straight member of the band, or maybe because her brother Ricky died of it in 1985. Or maybe simply because it needed to be talked about because it was killing people at an alarming rate and the then US President Ronald Reagan had been sitting idly by for four years since health officials had first become aware of the disease in 1981, only publicly acknowledging it on September 17, 1985. A silence, this one, that cost the lives of roughly 5,000 people solely in that same time frame.

Queerness in indie rock though, despite David Bowie’s attempts to bring to popularity Velvet Underground covers (one of the queerest bands of the time, in the sense that it moved with a transgressive, gay sensibility outside of conventional norms), assumed a subsidiary role almost until the ‘90s. It was in this decade that Pansy Division formed in San Francisco and gained popularity as the first gay alt-rock band, bringing queercore to the mainstream briefly. The early millennium was rough for indie musicians: surrounded by a pretty homophobic culture, many singers and band members were outed by the press, just like Bloc Party’s frontman Kele Okereke, who ended up distancing himself from indie altogether.

Taking a pause from mainstream popularity, indie rock seemed to disappear in the 2010s, only to return to popularity in the Trump Era as a no longer hetero-exclusive field, often turning identity politics and rebellion as the priority rather than concentrating the focus on the art.

Photo by Ed Bierman on Flickr

Metal (1960s-today)

It took a long journey of patient learning, but finally, we arrived at the queer history of metal, a genre so filled with myths and stereotypes that end up portraying it in the mainstream media as violent and aggressive and solely male and straight. The truth is that metal is the only genre with such a large plethora of subgenres that still identify under the same name, and some of them unfortunately are the things the mainstream media accuses them of. But metal is also everchanging, inclusive, and, as I hope I’ll be able to show you, queer.

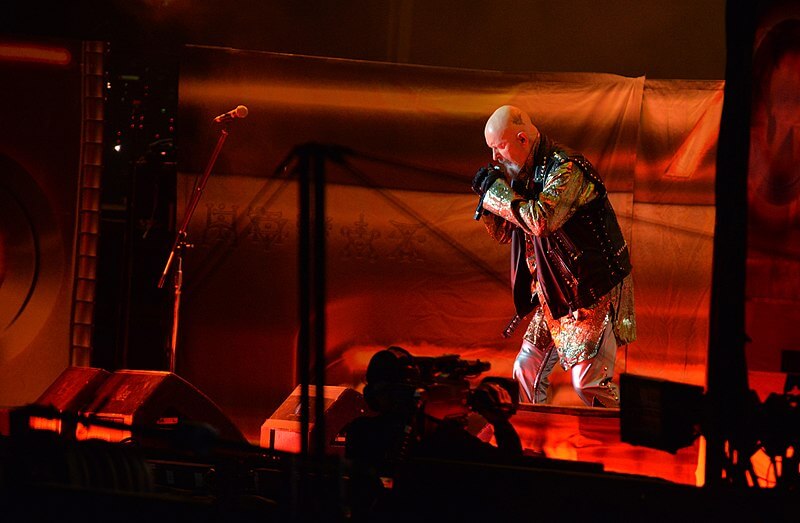

We can trace the genre’s origin back to Black Sabbath’s titular album in 1970, giving life to a kind of music composed of abrasive lyricism, fast, heavy blues guitar and screamed lines. Judas Priest, exactly a decade later, took the same formula, made it “campier” and gifted the world with the absolute classic masterpiece that is British Steel. It’s because of them, because of the gay frontman Rob Halford, that heavy metal adopted leather jackets and chains as its signature look. A look, make no mistake, that Halford based on what was in vogue in the ‘70s at London’s gay clubs. Unfortunately, the hostile climate would painfully force him into the closet, feeding his substance abuse and addiction, for a great part of his early career; it’s only in 1998 that Halford decided to come out in an MTV interview, forcing many fans to deal with personal issues and beliefs they were not ready to confront.

With the ‘80s and hair metal, other than a change in wardrobe (with tall hairstyles and tight pants), there’s also a rise in patriarchal views. It’s a weird time, filled with misogyny and homophobia, often associated with AIDS-related insults, but still with exceptions to this climate. The pop-metal pioneers Faith No More and their gay guitarist Roddy Bottum shocked the stiff mainstream press with explicit releases.

Like all the other genres seen so far, then, even in metal change is slow and fickle in its flow.

Photo by Selbymay on Wikimedia Commons

Through the 21st century, more and more people started accepting the diversity that the metal scene presented, a sight merely reflective of the situation of the rest of the world: today, being queer in metal no longer relegates performers and musicians to any kind of restrictions.

Throughout this piece, a little revisionist operation has taken place, because the term “queer” didn’t always have the meaning it has today. It’s effectively the imposition of a new idea onto a time period where the word was (to put it simply) a derogatory term against gays. But the ‘80s, together with the overtaking by the dance of the music scene, saw the appropriation of the word “queer” in a form of rebellious activism, essentially stripping it of its hateful powers, at least in part. Queerness is something people should just be able to “try on” without questions from those around them.

It’s difficult then, to find a precise moment and define it as the start of queerness in music, defining it as the instance that broke away from the past and gave space to a judgment-free era. It’s difficult because it doesn’t really exist: queerness and music are nothing more than a perpetual dance of mutual influence with history.

0 Comments